Hal Foster: The Confusion Machines of Doctor Höller

Originally published in theanyspacewhatever © 2008 The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York. Used by permission.

My objects are tools or devices with a specified use, which is to create a moment of slight confusion or to induce hallucinations in the widest sense. That is why I call them confusion machines.

Carsten Höller, 20011

“Since 1989 C. H. has dealt with major subjects such as security, the future, children, love, happiness, drugs, means of transportation and houses,” the psychologist Baldo Hauser has commented. “He is now focusing on doubt.” As an alter ego of the artist, Hauser ought to know, yet we might want to doubt him a little here, too. For Höller has long focused on doubt, and it remains central to his art, both as method and as effect.3

Take “security,” the first subject on the Hauser list. In fact, Höller is more interested in its opposites: threat and danger, risk and uncertainty. If we omit an initial group of paintings, his first work, produced in 1987, juxtaposes two emergency signs in such a way that the lighted arrows direct us in contrary directions at once—a security device turned into a confusion machine. Or consider “the future.” In 1991 Höller invited children in Berlin to demonstrate for the future outside the Reichstag, but only a few kids showed up (with rather pathetic handmade signs); apparently, less than two years after the fall of the Wall, the future looked doubtful as well.

This brings us to “children,” the third subject on the Hauser list, whom Höller sometimes treats with a skepticism that, as nasty as it is hilarious, surpasses doubt. For example, lest we think that kids are innocent, Höller offers us My First Drawings (1990), a set of five found photos of cute animals, all lined, scratched, or otherwise mistreated by an anonymous child. One implication of My First Drawings is that the fundamental urge in our markmaking is sadistic, and other projects turn this hypothetical cruelty back on kids, again with provocative results. In 1992 Höller did a series of pieces that pose as traps for children, including the child in each of us. In 220 Volt chocolate candies strewn on the floor lure us toward an electric cord plugged into the wall; the sinister seduction here suggests a Felix Gonzalez-Torres candy installation rewired by Chris Burden. 1992 also saw the production of a video titled Jenny that instructs its viewers in various ways to capture kids. It includes a drawing of a “child-catching car” that Höller realized a year later as a 1975 Land Rover, fitted with candies, nets, and a cage. Its title? Pest Control.

Carsten Höller: Pest Control, 1993. Foto: Wilfried Petzi

Before the police are called, let it be known that Höller, a father, is no pedaphobe; rather, these works stage the ambivalences in child-adult relationships, and test a few taboos in the process. In the world projected by Höller, we humans are hardly one big happy family; his idea of both the familial and the social is more agonistic—more realistic—than the benign versions of interaction often proposed by his peers associated with relational aesthetics. Consider “love,” the fourth subject on the Hauser list. In For Love’s Sake, a polemical text published in Der Standard in 1995, Höller, who was trained as an agricultural scientist, pits sexual pleasure “against the compulsion of genetic reproduction,” that is, against those pesky kids again. Our enforced responsibility to future society that children represent is here put in question.

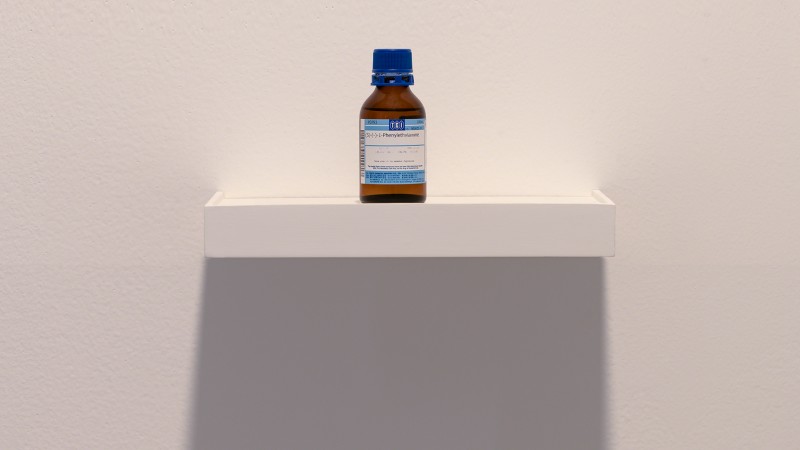

Höller also views “happiness,” the next subject on the Hauser list, in a less-than-sanguine manner; in fact, he often associates it with “drugs,” the sixth subject on the list, as though happiness sometimes required a pharmaceutical boost to be achieved. For instance, Pealove Room (1993), which offers two suspended harnesses for sexual coupling in midair, also comes with a vial of phenylethylamine (PEA), a hormone secreted by people in love, while Mushroom Case (1997) features psychotropic fly agaric mushrooms that spin psychedelically before our eyes. Yet Höller is no more a free-lover or a day-tripper than he is a child-hater: these pieces are settings not of love-ins or drug-trips but of virtual experiments in which the viewer is projected as both subject and object, collaborator and guinea pig.

Carsten Höller: Love Drug (PEA), 1993-2006. Foto: Attilio Maranzano

Höller thus probes contact-zones—between adults and children, love and reproduction, reality and hallucination—that are well patrolled by guardians of society. In a further topos (which might fall under “houses” on the Hauser list), he probes other boundaries—between humans, plants, insects, birds, and animals—that are also assumed to be secure. (I said Höller was trained as a biologist; more precisely, he has a Ph.D. in phytopathology from the University of Kiel, with a dissertation on the function of scent in the attraction of certain insects to each other as well as to certain plants.) If he views society as more fraught than do some of his artist colleagues, so too does he see species as more fluid. For example, in Acné (1995) Höller watered an orange tree with a solution containing human smells, while in Garden of Love (2004) he filled a greenhouse with a vine, Solandra maxima, whose scents are believed to incite amorous feelings in people. Along the way Höller has also done various pieces involving not only the training but also the breeding of birds (here Doctor Höller recalls Doctor Moreau a little); and, for a few years in the late 1990s, he collaborated with Rosemarie Trockel on several structures that placed people in close proximity with other species. For instance, Mückenbus (1996) is a van designed to commingle mosquitoes and humans (museums are not eager to put it into action), and House for Pigs and People (1997) is a habitat in which viewer-visitors contemplate porcine doings from behind a one-way mirror.

Höller is best known for the last of the Hauser topoi to be mentioned here, “means of transportation,” which we should read as “transport”—transport in the sense of ecstasy, of a passage of the self through the senses, beyond the senses. Important to Höller in this respect is the typology of play put forward by the Surrealist philosopher Roger Caillois in Man, Play and Games (1958), in particular the category of play concerned to produce vertigo “to momentarily destroy the stability of perception and inflict a kind of voluptuous panic upon an otherwise lucid mind.”4 Perceptual instability and voluptuous panic are precisely what the confusion machines of Doctor Höller work to induce.

Carsten Höller: Expeditions-Rucksack, 1995/2000. Foto: Carsten Höller Studio.

Perceptual instability is already the aim of Kit for the Exploration of the Self (1995), a reprise of a device invented a century ago by the American psychologist George Stratton, here in the form of geekily protuberant goggles that turn the world upside down—that is, that reverse the automatic reversal, in our brain, of what our eyes in fact see. (Höller has produced such topsy-turviness in actual space, too, as in his Upside Down Mushroom Room of 2000, in which the rotating fly agarics of Mushroom Case reappear, vastly enlarged, brightly colored, and suspended stool down from the ceiling.) Meanwhile, voluptuous panic is already the aim in Flying Machine (1996), a contraption that, rather than invert the world optically, whirls the harnessed viewer-visitor bodily around a space. Related confusion machines include Spinning Top (1996) and Sphere (1998), respectively a top (made of fiberglass, fabric, and steel) and a sphere (made of aluminum, or acrylic glass, and steel) large enough to contain the viewer-visitor and to spin or roll him or her about a room. These, too, are means of transport designed to produce “a mingled sense of joy and senselessness.”5 Often enough, when Höller is not concerned to “transport the artwork inside the once-passive bodies of spectators,” as with his hormone and mushroom pieces, say, he is concerned to transport bodies inside the artwork, as with these pieces here. In both cases it is the viewer-visitor, not the object, that is most subject to transformation.6 Such projects foreground the fundamental proposal of his work: a reimagining of the space of art as a laboratory of the human. The human is a category that Höller plays with as in a game, probes as in a test, or deranges as in a semi-mad experiment, and it is in this double crossing—of gallery and lab and of game, test, and experiment—that the primary interest of his art lies. In this blurring of game, test, and experiment, the viewer-visitor is also blurred: he or she becomes a hybrid of player, datum, and analyst in an event-space in which the goal is less the understanding of the object than the intensification of the subject (Höller calls this effect by various names: doubt, confusion, perplexity, euphoria, joy and senselessness, delight and madness…).7

To this end Höller has concentrated on two types of confusion machine over the last decade. The first type involves light installations that produce optical disruptions; for example, Light Wall (2000) is a vast panel of many lights programmed to pulse in a way that creates hallucinatory effects. Sometimes in such works Höller plays on the “phi phenomenon,” as identified by the German psychologist Max Wertheimer a century ago, in which the viewer-visitor perceives, between the alternation of two lights, a third one that does not in fact exist (he has also explored the phenomenon in video and film installations). Sometimes these light pieces are quite immersive. For instance, Y (2003) is a tunnel made of 16 large aluminum rings lined on the inside with bulbs that are illuminated in sequence so that the rings appear to rotate. Drawn by the lights into the tunnel, which does indeed take the form of a horizontal Y, the viewer-visitor is quickly disoriented, and the proverbial fork-in-the-road becomes a matter of any-way-out. Such confusion machines suggest an updating of the optical experiments of Duchamp by way of the constrictive corridors of Bruce Nauman.8

The second type of confusion machine features fairground carousels that Höller has refunctioned or new slides that he has commissioned. The first of his carousels appeared in 1999, a merry-go-round taken from a Leipzig amusement park like a giant readymade, which Höller then set in motion at a hypnotically slow rate—a simple adaptation that transformed this everyday ride into an exotic means of transport to an alternative world, a different space-time.9 The first of the slides appeared in 1998 at the Berlin Biennial, where it served simply to connect the different floors of one exhibition venue. Quickly, however, the presentation of both kinds of confusion machine became more elaborate. The most spectacular display of the rides occurred in summer 2006 at Mass MoCA, the cavernous spaces of which were transformed into an uncanny cemetery of fairgrounds past. And the most spectacular version of the slides occurred in winter 2006–07 at the Tate Modern, where five stainless-steel slides, from 16 to 58 meters in length, snaked down the vast Turbine Hall to connect the different levels of the museum to the ground floor. Many braved the ride.

Test Site, Tate, London, 2006. Foto: Attilio Maranzano

What does it mean to bring the fairground and the playground into the space of the museum? On the one hand, it reopens the realm of the aesthetic, as it was originally defined in the Enlightenment, to the world of the senses (i.e., before it was restricted to the experience of the arts); more, it literalizes the dimension of play held to be central to the aesthetic impulse since the Enlightenment as well.10 On the other hand, this commingling of art and play appears to deliver both registers, the aesthetic and the ludic, to the world of spectacle once and for all; at the very least, it suggests that these orders cannot be even imagined as separate today.11 Indeed, Jessica Morgan, the Tate Modern curator who oversaw the Turbine Hall slide project, proclaimed it “the ultimate realization of the twentieth-first-century art museum as entertainment zone.”12

Yet one need not affirm this development to posit another potential within it. For in such projects Höller also follows in a long line of artists, from Édouard Manet, Georges Seurat, and Robert Delaunay, to Richard Hamilton, Andy Warhol, and Thomas Hirschhorn, who, rather than retreat from capitalist modernity, take up its typical spaces and objects—the café-cabaret, the circus, the fairground, luxury commodities, celebrity images, retail kitsch—as the very stuff not only of everyday life but of advanced art as well. For such artists distraction and spectacle—or, in Höllerian terms, joy and senselessness, delight and madness—are among the given materials of any pertinent practice, and sometimes these artists propose not merely an ambivalent deployment of such conditions but a go-for-broke exacerbation in the hope that this extreme mimesis might reveal an other side of these conditions, a new way of being in the world.

The dangers of this strategy are also clear. Mimetic exacerbation can easily flip into mere affirmation, indeed into facile celebration. It is often said that a chief symptom of postmodern subjectivity is a manic alternation between intense feeling and no-feeling-at-all, a paradoxical waxing and waning of affect; and clearly Höller is concerned to create out of such affective extremes.13 But can one work effectively with doubt and confusion, perceptual instability and voluptuous panic, when these states often seem more normative than exceptional today (ours is often called a “risk society”)? Should one seek to expand the aesthetic when postmodern culture appears to aestheticize everything for us already? Can one reclaim play in a culture that seems given over to the scripted game (in a culture, that is, in which millions of us sit, day and night, attached to virtual computer worlds)? Can one reclaim experiment in a society that appears given over to permanent testing (in a society, that is, in which many of us are constantly examined and reexamined, trained and retrained—in a society at the mercy of a “test drive”)? It is not the least of his achievements that Carsten Höller compels us to ponder such questions.

Fodnoter

1 Carsten Höller quoted in Hans Ulrich Obrist, Interviews, vol. 1 (Milan: Charta, 2003), p. 409.

2 Ibid., pp. 403–04. I wonder if Baldo Hauser is any relation to Kasper Hauser.

3 As a method, two kinds of doubt come immediately to mind, the philosophical one associated with Descartes and the perceptual one associated with Cézanne (I have in mind the great Merleau-Ponty essay “Cézanne’s Doubt”). But doubt in Höller is not the basis of a modern truth, as it is in these others. Nor does it lead to the groundlessness of a postmodern relativism. For Höller “These doubts of how things appear to be are not . . . the same as skepticism or as doubting everything. It’s not at all interesting to doubt everything.” Ibid., p. 405. The alter ego and the pseudonym are also ways Höller introduces doubt, here, obviously enough, regarding identity. Apart from Baldo Hauser, there are Baldo Hanser, A.J. Florizoone, Karsten Höller…

4 Roger Caillois, Man, Play and Games (1958), cited in Carsten Höller, Test Site: Source Book (London: Tate Modern, 2006), p. 77. Höller published his own Game Book in 1998, a compendium of games from the simple to the fantastic and the absurd.

5 Höller quoted in Carsten Höller, ed. Francesco Bonami (Milan: Electa, 2007), p. 44.

6 Jennifer Allen, “20/20,” in Carsten Höller: Logic, ed. Mark Francis (London: Gagosian Gallery, 2005), p. 24.

7 As Allen nicely puts it, “the exceptional experience of the experiment is lived out instead of being used to define a rule.” Ibid., p. 6. This living-out can be literal: in his installation for the present exhibition, the viewer is invited to spend the night within the museum, on a circular platform that holds three circular “tables” of various sizes, each of which revolves very slowly. In one register of this intervention the famous Guggenheim Museum spiral is put into motion; in another register the museum is blurred a little with the hotel.

8 Duchamp admired Raymond Roussel, and perhaps there is also an echo here of his fantastic machines in, say, Impressions of Africa (1910), which are also not always pleasant.

9 Inversely, in Test Site: Source Book Höller includes a short story by H. G. Wells, “The New Accelerator (1943?),” in which the protagonists take a drug that accelerates them in such a way that the rest of the world appears all but arrested.

10 On the first point see Jennifer Allen, “Uncommon Senses,” Parkett, 77 (2006): p. 39. Play is seen as fundamental to art from Friedrich Schiller to Sigmund Freud and Johan Huizinga, whose Homo Ludens (1938) was influential to the Situationists, Archigram, and other postwar groups concerned with the ludic.

11 There are precedents here too, such as the Exploding Plastic Inevitable events arranged by Andy Warhol and associates.

12 Jessica Morgan, “Foreword,” in Carsten Höller Test Site (London: Tate Modern, 2006), p. 13.

13 I have in mind, of course, the writings of Fredric Jameson on postmodern culture, but this oscillation was already a topos at the moment of Pop art.